Multivariate Testing

Table of Contents

Multivariate testing (MVT) is an experimentation method used to measure how multiple design elements and their variants interact within a single test environment, enabling analysis of which combinations and interactions most effectively achieve a defined objective. Typical objectives include improving conversion rate, click-through rate, task completion rate, revenue per session, and interaction depth metrics such as dwell time and form progression.

Unlike single-variable tests that compare one modified element against a baseline condition, multivariate testing applies factorial experimental design and cell-based traffic allocation. Each variant corresponds to a specific combination of page elements (e.g., headline × layout × CTA), and traffic is segmented so that each user session is exposed to only one combination.

MVT is most effective when the goal is to understand how design elements jointly influence performance, not simply to identify a winning option. Its applicability depends on sufficient traffic volume, a disciplined setup, and careful risk assessment.

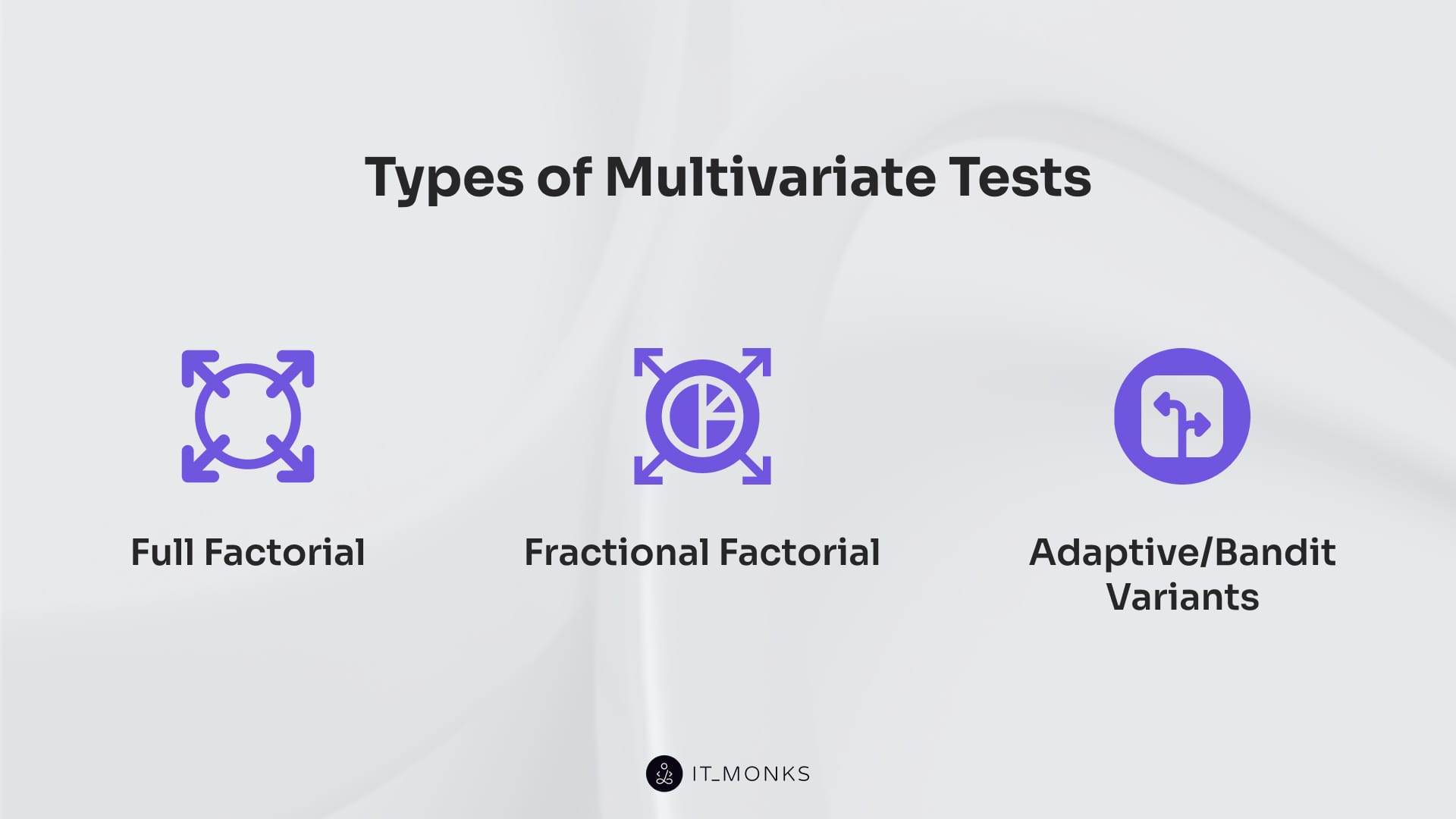

Multivariate testing is implemented through distinct design types: full factorial, fractional factorial, and adaptive/bandit models, which differ in how many variable combinations are evaluated, how interaction effects are estimated, and how traffic is allocated across variants.

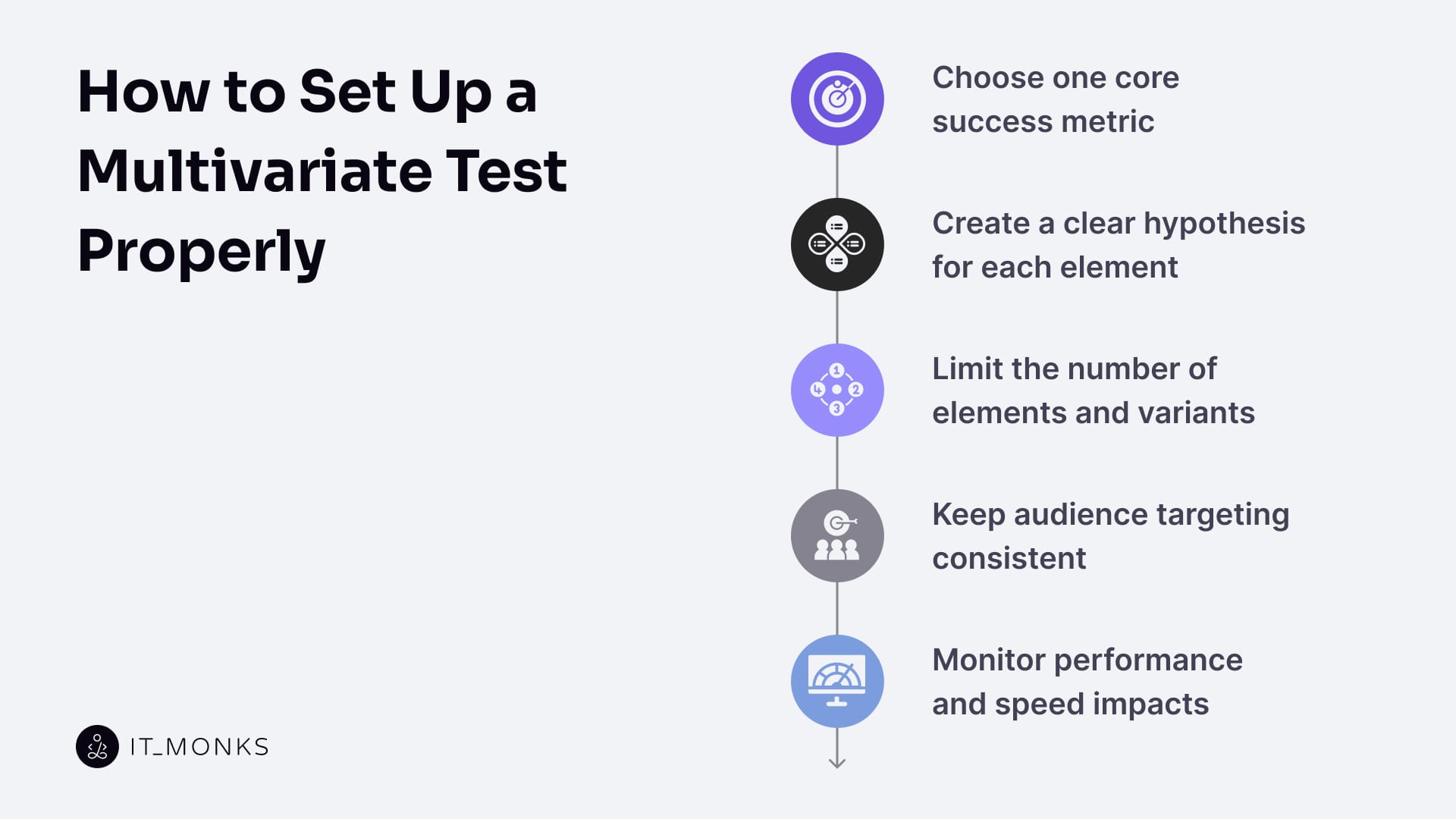

Effective MVT execution requires a controlled setup: selecting a single primary success metric (such as conversion rate or revenue per session), defining explicit interaction hypotheses, limiting the number of test variables to prevent matrix explosion, and continuously monitoring cell-level sample size, traffic balance, and confidence stability throughout the test lifecycle.

What is Multivariate Testing?

Multivariate testing (MVT) is a structured digital experimentation method that measures how multiple test elements and their variant combinations interact to influence user behavior and performance metrics. In contrast to single-variable approaches (such as those described in our A/B testing guide), MVT evaluates multiple changes simultaneously to understand how combinations of variables affect outcomes like conversion rate or engagement signals.

At a technical level, multivariate testing operates via factorial logic: each test variable is treated as an independent factor with defined levels (variants), and the experiment evaluates outcomes across combinations of those factors.

Each test element is assigned a set of modifiable variants, which are combined into predefined scenarios within a controlled experimental framework. Traffic segmentation distributes users across these combinations while maintaining control conditions, enabling the system to isolate statistical interaction effects rather than simple winner–loser comparisons. This design allows multivariate testing to evaluate probabilistic outcomes and reveal which combinations of elements drive meaningful behavioral change with statistical confidence.

What Multivariate Testing Is Good For?

Multivariate testing is effective for analyzing how combinations of design variables jointly influence measurable outcomes, rather than assessing changes in isolation. Its primary function is to detect interaction effects between elements within the same environment and to identify which variable groupings produce statistically significant performance differences.

A core application is identifying variant combinations that reliably improve conversion metrics. By evaluating a structured test matrix, multivariate testing compares how grouped elements (such as headline wording combined with visual hierarchy or layout structure) affect user response patterns. This allows interaction effects to be isolated, where individual changes show limited impact alone but generate measurable uplift when combined.

The method is particularly valuable for optimizing complex interfaces in which multiple elements influence a single decision path. In these contexts, multivariate testing reveals how micro-interaction metrics, including click-through behavior, dwell time, and form progression, shift when variables are adjusted together. This reduces attribution ambiguity by showing how combined design changes shape user flows, rather than assigning outcomes to a single dominant factor.

Multivariate testing also supports behavior modeling through segmentation-based analysis. By distributing traffic across variant combinations, it enables comparison of how different user segments respond to identical structural changes. These insights inform confidence-based optimization decisions for heterogeneous audiences and often feed into continuous improvement cycles within CRO-focused workflows.

What Multivariate Testing Is Not Good For?

Multivariate testing is not suitable for low-traffic, time-sensitive, or narrowly scoped experiments, as its complexity can yield unreliable or delayed results.

A primary limitation occurs in low-traffic environments. As the number of variant combinations increases, available traffic is distributed across more cells, reducing exposure per variant. This fragmentation leads to insufficient sample sizes, unstable confidence estimates, and a higher risk of false inference.

Multivariate testing also performs poorly in urgent decision cycles. Its factorial structure requires longer convergence periods to reach statistical confidence, which delays insight when rapid validation or immediate release decisions are required. In fast-moving environments, simpler testing models deliver faster and more actionable feedback.

Another mismatch arises when the scope of the hypothesis is narrow. If the objective is to validate a single design element in isolation, multivariate testing overcomplicates the experiment by expanding the variant matrix. In these cases, A/B testing provides clearer attribution by directly comparing a control against a focused modification.

Multivariate testing is not a substitute for exploratory or qualitative analysis. It cannot explain user intent, emotional response, or attention distribution. When the goal is to identify focus patterns, hesitation points, or visual engagement, behavioral research methods offer higher signal clarity. In early-stage diagnostics, approaches such as those outlined in the heat map guide often outperform multivariate testing by revealing interaction patterns before formal hypotheses are defined.

What Are the Types of Multivariate Tests?

Multivariate testing includes three primary design types: full factorial, fractional factorial, and adaptive/bandit, each defined by how variant combinations are selected, evaluated, and interpreted within a structured test matrix.

When grounding these multivariate approaches against single-variable experimentation, the split test guide provides the necessary baseline by explaining fixed-allocation testing, strict variable isolation, and direct control–variant comparison.

Full Factorial

A full factorial test is a multivariate testing approach that evaluates every possible combination of all defined variants across all selected design elements. This complete coverage model constructs a fully expanded test matrix that represents each element-variant intersection, enabling exhaustive sampling of how variables behave both independently and in combination.

Because every variant combination is tested, the full factorial design provides high-resolution mapping of interaction effects. Each combination receives segmented exposure across user groups, which allows the test to measure subtle performance differences and produce high-fidelity statistical output

The precision of this method comes at a cost. As factorial scaling increases combinatorial density, the test requires substantial traffic volume and extended runtime to ensure statistically significant results for each cell in the matrix. For this reason, full factorial testing is most appropriate in controlled, high-traffic environments where insight granularity and experimental clarity outweigh concerns about speed or resource intensity. Within the multivariate testing spectrum, it functions as the baseline model for total interaction analysis and maximum analytical completeness.

Fractional Factorial

A fractional factorial test is an efficiency-oriented multivariate testing model that evaluates only a strategically selected subset of all possible variant combinations. Rather than exhausting the entire test matrix, this approach applies controlled reduction to limit combinatorial scope while preserving the ability to infer main effects and selected interaction effects.

By intentionally selecting a variant subset, the method reduces test load and improves traffic efficiency without abandoning structured experimental logic. This matrix simplification relies on design assumptions that enable meaningful statistical inference from partial exposure while retaining insight as the number of tested combinations decreases. The result is faster convergence and lower resource requirements than with full-coverage models.

Fractional factorial testing is suited to environments where total-combination testing is impractical due to traffic or time constraints, yet multivariate insight is still required. It represents a deliberate balance between analytical depth and feasibility, limiting interaction visibility in exchange for manageable complexity and scalable execution, positioning it as an intermediate node between exhaustive and adaptive testing strategies.

Adaptive/Bandit Variants

Adaptive multivariate testing, often implemented through bandit variants, represents a dynamic alternative to fixed matrix designs by continuously adjusting test exposure based on live performance signals. Unlike static factorial models, adaptive testing does not distribute traffic evenly across all variants throughout the test.

These systems begin by exploring available variant combinations, then rapidly shift traffic toward those showing stronger outcomes. A learning algorithm reallocates exposure in real time, prioritizing combinations that generate higher conversion rates or stronger performance signals. This traffic allocation strategy creates a continuous feedback loop in which the test learns, adapts, and optimizes while running, emphasizing the exploitation of successful variants over uniform comparison.

The trade-off is analytical depth. Because exposure becomes performance-weighted, adaptive testing limits the ability to fully analyze interaction effects or understand underperforming combinations. As a result, this method prioritizes optimization speed and conversion rate over comprehensive diagnostic insight. Within the multivariate testing hierarchy, Adaptive/Bandit variants occupy the performance-first position, best suited for high-velocity environments where rapid gains and responsiveness are more critical than complete interaction mapping.

How to Set Up a Multivariate Test Correctly?

Pick One Primary Metric

Pick one primary metric by selecting the single performance indicator that best represents the test objective you’re trying to improve. This metric serves as the performance anchor for the entire experiment: the multivariate test evaluates variant outcomes relative to this baseline, and every combination is ranked by its impact on the same success criteria. Good primary metrics are conversion events or behavioral targets that map directly to the decision you’re optimizing, for example, form submissions, checkout completions, click-through rate on a key action, or time-on-task for a critical flow.

Keep secondary metrics visible, but don’t let them compete with the outcome focus. Supporting signals (like scroll depth or bounce behavior) can help you interpret why a result happened, but the final decision should remain aligned to the primary metric so the test doesn’t drift into metric ambiguity or split-focus conclusions.

Define a Clear Hypothesis Per Element

Define one hypothesis per element by writing a specific, testable expectation that connects a single element change to a measurable outcome shift. Each hypothesis should follow a simple change-response logic: change → expected user interaction signal → predicted impact on the primary metric. For example, a headline variant might increase clarity and therefore improve completion rate, while a button variant might influence click behavior and therefore raise the conversion event count.

This element-level structure is what keeps multivariate learning interpretable. When each test element is assigned a singular directional expectation, you can associate observed performance outcomes with the intended variant behavior instead of guessing after results converge. Write hypotheses before the test begins, retroactive hypotheses distort interpretation by redefining success after the data are already known.

Set the Elements and Variants Limits

Set limits by selecting only high-impact test elements and capping the variants per element to prevent matrix complexity from overwhelming traffic allocation. Every additional element or variant increases combinatorial load, expands the test matrix, and lowers the user exposure rate per combination, creating exposure dilution and slowing convergence. A disciplined configuration prioritizes elements with clear conversion impact and limits variants to what your traffic volume can support within the available runtime.

The goal is result resolution, not maximum possibility coverage. If variant sprawl fragments exposure across too many combinations, statistical integrity drops and interpretation becomes noisy. Tight scope control preserves data clarity, speeds learning, and keeps interaction density at a level where outcomes remain actionable.

Use Consistent Targeting

Use consistent targeting by defining the target audience once and keeping exposure conditions stable across all variants for the full test duration. Multivariate tests depend on comparison validity, which requires segment parity: each variant combination should receive an equivalent traffic mix across key user conditions such as device type, entry context, geography (if relevant), and behavioral state (new vs. returning). When targeting shifts mid-test, environmental variation becomes an unintended variable and distorts performance signals.

Consistent targeting does not mean “broad targeting.” It means controlled and uniform exposure control logic. Decide the segmentation rules before launch, standardize them across all test groups, and keep them fixed so that observed metric differences can be attributed to design elements rather than audience drift.

Watch for Performance Impacts

Watch for performance impacts by monitoring whether the test infrastructure introduces load latency, rendering instability, or interaction delays that change behavior independently of the variants. Multivariate tests often add script overhead, variant swapping, or client-side rendering logic, which can trigger render blocking, DOM shifts, reflow events, and slower time-to-interaction, especially across varying device performance. If the page becomes slower or less stable, users may abandon or hesitate due to friction, and the test ends up measuring performance degradation instead of design effect.

Treat performance stability as part of experimental integrity. Regularly measure responsiveness and interaction timing during the run, and reduce test-induced friction where possible so the comparison remains fair: [Stable delivery] ensures [clean behavioral signals], which protects metric accuracy and keeps variant differences meaningful.

What Are Common Mistakes in MVT Set Up?

Common mistakes in multivariate test setup include failing to define a single primary metric, skipping element-level hypothesis definition, overloading the element–variant matrix, applying inconsistent targeting, neglecting performance behavior, and drawing conclusions from partial data before statistical convergence.

A frequent and damaging error is skipping the definition of a single primary metric. When multiple success criteria compete, evaluation becomes incoherent: variants appear to “win” on different measures, and no clear decision baseline exists. This measurement breakdown introduces semantic drift, making it impossible to confidently attribute results to improvements in a specific user behavior or outcome.

Another common failure is ignoring the hypothesis definition at the element level. Without a clear expectation for how each element should influence behavior, variant outcomes lose interpretive meaning. Teams end up observing performance changes without understanding causality, misattributing effects, or retrofitting explanations after the fact.

Overloading the element-variant matrix is also a persistent issue. Adding too many elements or variant fragments to the traffic across an expanded combination set causes exposure dilution and low-confidence results. This testing scope failure stretches convergence timelines and increases structural noise, often producing inconclusive outcomes rather than deeper insight.

Inconsistent targeting configuration further undermines validity. When audience segments, traffic sources, or user conditions shift during a test, performance differences reflect exposure variability instead of design impact. This inconsistency introduces test noise and invalid attribution, making comparisons unreliable even if metrics appear statistically significant.

Neglecting performance behavior is another setup mistake with downstream consequences. Test scripts or variant renderings that degrade load time or interaction timing alter user behavior, contaminating behavioral signals and distorting data accuracy.

Premature data interpretation, drawing conclusions before sufficient data accumulates, invalidates otherwise sound setups. Early trends are unstable, and acting on partial signals leads to false confidence and poor decisions.

How to Interpret Results of MVT?

Interpreting multivariate test results means systematically aligning observed variant performance with the primary metric, the original element-level hypotheses, and the controlled exposure conditions used during the test.

The process starts by referring to the primary metric and comparing which variant combinations produced meaningful, sustained movement in that outcome, positive or negative, rather than short-lived spikes.

From there, analysis should trace results back to element-level hypotheses. For each element, confirm whether the observed behavioral signals matched the predicted direction and magnitude. If a variant performed well but contradicted its hypothesis, the insight lies in understanding why the behavior changed, not simply celebrating the outcome. This hypothesis traceability preserves behavior attribution and keeps learning grounded in test intent rather than surface metrics.

Next, focus on interaction effects. Multivariate testing often reveals that an element’s impact depends on the presence of another change, so interaction mapping across combinations is essential. Patterns that recur across segments or configurations signal genuine relationships, while isolated wins may indicate noise. Segment behavior analysis can deepen this step, especially when paired with structured approaches to user behavior analysis, helping confirm whether effects are consistent across user conditions.

Before drawing conclusions, validate reliability by checking statistical confidence. Ensure sample sizes are sufficient, confidence thresholds are met, and performance trends remain stable over time. Reliable interpretation depends on statistical stability and exposure sufficiency; without them, apparent gains risk being artifacts of chance.

Contact

Don't like forms?

Shoot us an email at [email protected]