WordPress File and Directory Structure

Table of Contents

The WordPress file and directory structure governs the internal operations of every WordPress website, serving as the architectural foundation that defines initialization flow, plugin and theme execution, and overall system bootstrapping behavior. As the framework for PHP file processing and server-side logic, it segments the file system into core directories, customization zones, and operational entry points, each contributing to the deployment structure and runtime hierarchy.

File and directory structure includes both modifiable and protected paths that dictate how WordPress stores assets, loads configuration files, and executes routing logic. Core files located in system-managed directories, such as /wp-admin/ and /wp-includes/, handle backend processing and internal functions and are not intended for direct modification. Root-level files (including critical components like wp-config.php) define access permissions, environmental variables, and connection parameters that govern the site lifecycle from initialization to content rendering.

For developers, understanding the interactions among these directories, identifying where customization is appropriate, and recognizing the role of system-level files are essential for managing version control, securing update processes, debugging execution flow, and building extendable themes and plugins within the /wp-content/ boundary.

Every architectural decision in WordPress development ultimately traces back to this structure, whether isolating deployment-sensitive components, maintaining reliable backups, or integrating Git into the development workflow.

How Can a Developer Access WordPress Files and Directories?

Developers access the WordPress file system through multiple pathways depending on the project environment, typically using local development stacks, FTP/SFTP clients, SSH sessions, or Git-based workflows. Each method provides a level of file-level control necessary for editing code, managing deployment structures, and interacting with WordPress directory hierarchies.

In local development environments such as Docker, LocalWP, MAMP, or XAMPP, developers interact directly with the file system, navigating into directories, editing theme and plugin code, and testing runtime behavior in real-time.

For remote environments like staging or production, access shifts to secure methods: FTP or SFTP for file transfers, and SSH for command-line operations and advanced deployment tasks. When version control is enforced, especially in Git-based workflows, file access is often scoped to /wp-content/ only, preserving the update integrity of core directories.

Across all workflows, the developer’s primary access points remain rooted in /wp-content/: customizing frontend behavior in /themes/, managing extensions in /plugins/, or validating uploads in /uploads/. While /wp-admin/ and /wp-includes/ may be explored for debugging or reference, they remain read-only zones governed by WordPress core.

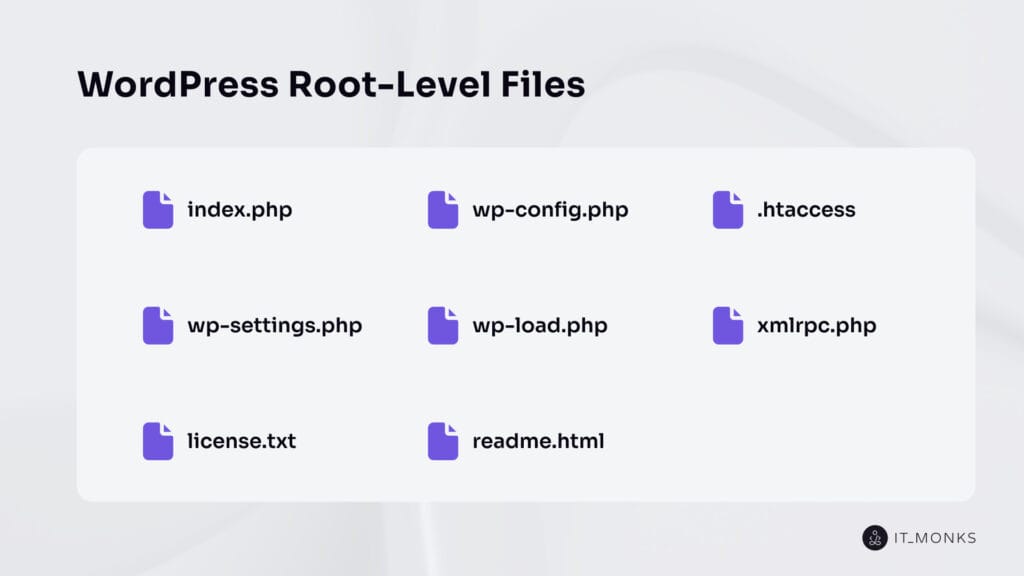

What Are the WordPress Root-Level Files?

WordPress root-level files reside in the base directory of a WordPress installation, the top-most path that loads when accessing the site’s root domain. These files are not nested within any subdirectories; instead, they are positioned at the system’s entry point, where they initiate configuration, load core processes, and handle incoming server requests. Unlike files inside /wp-content/, /wp-admin/, or /wp-includes/, root-level files operate globally and early in the execution sequence, forming the structural surface of the WordPress application.

The standard root-level files include:

- index.php

- wp-config.php

- .htaccess

- wp-settings.php

- wp-load.php

- xmlrpc.php

- license.txt

- readme.html

Positioned at the interface between server logic and WordPress internals, these files form the architectural boundary between platform logic and external WordPress environment configurations.

index.php

index.php in the root directory serves as the primary request entry point for a WordPress website when server-side rewrite rules are configured to funnel all traffic through a single executable. It includes wp-blog-header.php, which, in turn, loads the entire WordPress environment, initializing core logic and routing behaviors.

Despite sharing its name with the theme-level file, this root-level index.php is not involved in content rendering or theme templating. It strictly governs execution flow and route handling at the system level.

Developers often misinterpret its role, overlooking its position as a foundational load sequence trigger.

wp-config.php

wp-config.php is the central configuration file in the root directory that defines how WordPress connects to its database and loads critical environment variables during startup. This file executes before any core logic and exposes constants that govern authentication, debugging, table structure, and memory handling.

As the bridge between the file system and runtime, wp-config.php controls the deployment-specific values that dictate application behavior across environments. Its presence is mandatory, but its contents are often environment-specific, making it a non-versioned file and a sensitive component in any WordPress deployment. Any modification here directly affects how WordPress initializes, meaning developers must treat it as an entry-layer control point, not a general-purpose config panel.

.htaccess

.htaccess is a server-level configuration file used by Apache to override directory behavior and apply rewrite rules that influence how WordPress routes incoming requests. During permalink setup, WordPress modifies this file to enable clean URLs by rewriting paths to be handled by index.php. Though not part of the core PHP stack, .htaccess affects the request lifecycle by enabling features such as custom redirects, security headers, and URL rewriting.

Developers working in Apache environments must carefully preserve and audit this file. Misconfigurations can result in broken routes, infinite loops, or HTTP 500 errors. It’s an external yet integrated layer of file-based control that WordPress depends on for front-facing URL management.

wp-settings.php

wp-settings.php is the core initialization file that boots the WordPress runtime after the environment is defined by wp-config.php and wp-load.php. This file loads essential system components, initializes default constants and classes, sets up the global $wp_filter structure for hooks, and executes active plugins and theme loading. It marks the point at which WordPress transitions from a configuration state to an operational, extensible runtime.

Developers do not modify wp-settings.php directly, but its execution sequence is critical in tracing plugin behavior, theme rendering issues, and hook registration. By understanding where wp-settings.php sits in the execution chain, developers gain insight into the timing and scope of everything that follows in a WordPress application lifecycle.

wp-load.php

wp-load.php is a core loader file that initializes the WordPress environment from files or scripts outside the main application flow. It’s included via entry points such as index.php, xmlrpc.php, or custom CLI tools to bridge external code into the core WordPress runtime. Its role is to locate the WordPress install path, set preliminary system constants, and include wp-config.php, which then cascades into the full boot sequence.

For developers, wp-load.php functions as a runtime entry hook, enabling background tasks, custom endpoints, or diagnostic scripts to connect to WordPress without duplicating environment logic. Tracing how this file fits into execution pathways is vital for debugging complex integrations and maintaining consistency across deployment targets.

xmlrpc.php

xmlrpc.php is a legacy gateway file that enables communication between external systems and WordPress using the XML-RPC protocol. Historically, it supported remote publishing tools, mobile app access, and pingbacks, long before the REST API was introduced.

While its functional relevance has declined, xmlrpc.php remains a publicly exposed access vector and is frequently targeted in brute-force and DDoS attempts. Developers must recognize its presence as a potential liability: it’s often monitored, restricted, or disabled in production unless explicitly needed. Although largely deprecated, this file still processes remote commands and must be accounted for in any secure deployment strategy.

license.txt

license.txt is a non-executable file located at the WordPress root that contains the full text of the GNU General Public License (GPL v2). This open-source license governs WordPress usage and distribution. It has no runtime purpose and does not impact application performance or behavior.

Because it is publicly accessible, bots and fingerprinting tools often use it to confirm a site is running WordPress. Although harmless in isolation, its visibility may contribute to automated reconnaissance. In production, it’s common for developers to restrict or remove license.txt as part of deployment hygiene to reduce unnecessary exposure.

readme.html

readme.html is a static file included in the WordPress root directory that contains version metadata, project information, and links related to the WordPress CMS. It is not part of any runtime logic and does not influence application behavior.

Readme.html is publicly accessible and often exposes the exact WordPress version in use, making it a high-value target for bots and vulnerability scanners. Since it provides no benefit in production environments and leaks installation metadata, developers typically remove or restrict access to this file as a best practice to reduce surface-level exposure and improve deployment discipline.

Which Are the Main WordPress Directories?

The WordPress directory structure organizes the system’s architecture into three main directories: /wp-admin/, /wp-includes/, and /wp-content/. Each of these directories defines a distinct execution zone within the WordPress environment, aligned with specific responsibilities across development, configuration, and runtime behavior.

- /wp-admin/ contains the backend administrative interface: the scripts, stylesheets, and logic that govern site management and dashboard functionality.

- /wp-includes/ houses the internal runtime libraries, class definitions, and core functions that form the foundational logic of WordPress; it is where non-editable system code resides.

- /wp-content/ supports all developer-facing customizations, including plugins, themes, media uploads, and content-specific code. It is the only directory intended for routine modification.

What Does the /wp-admin/ Directory Contain?

The /wp-admin/ directory contains the system-level logic, core files, and assets that render and execute the WordPress administrative interface. In this backend environment, site administrators manage content, settings, users, plugins, and themes. As the control hub of the WordPress dashboard, this directory handles backend HTTP requests, enforces user permissions, and routes administrative actions through a tightly regulated execution pipeline.

Internally, /wp-admin/ includes essential PHP entry points (such as admin.php and index.php), bundled JavaScript and CSS assets for interface rendering and interaction, and AJAX handlers that support dynamic behaviors within the admin context. It integrates with the /wp-includes/ directory to access runtime functions and enforce permission checks during administrative operations.

From a development perspective, /wp-admin/ is considered part of the non-editable core. Direct modification of files within this directory is discouraged, as it compromises WordPress’s update-safe architecture. Instead, developers are expected to extend or customize backend functionality using WordPress’s plugin system, admin-specific hooks, and REST or AJAX APIs.

What’s Inside the /wp-content/ Directory?

The /wp-content/ directory stores all custom functionality, assets, and user-generated content within a WordPress website, making it the only directory explicitly intended for developer interaction and modification. Structurally, it serves as the customization layer of the WordPress architecture, containing the themes, plugins, and media that define a site’s appearance, behavior, and dynamic assets.

This directory is preserved across core updates and remains untouched during version upgrades, supporting safe deployment workflows and enabling structured content evolution. Its stability across updates makes it the primary focus for version-controlled development, staging synchronization, and production backups, as it is the sole directory where content changes are expected and frequent.

Within /wp-content/, WordPress maintains four core subdirectories:

- /plugins/ for feature extensions,

- /themes/ for layout and design logic,

- /uploads/ for media storage,

- /mu-plugins/ for autoloaded, non-optional plugins.

These subpaths govern how WordPress executes custom code, renders the frontend, and manages assets across environments.

For developers, /wp-content/ is the operational hub of site customization, a directory that demands precision, structural discipline, and consistent version control. Each component will be examined in detail in the following sections.

/plugins/

The /plugins/ directory is the designated subfolder within /wp-content/ where WordPress stores all standard plugins, both custom and third-party. It serves as the primary extension point for enhancing WordPress functionality across both the admin interface and frontend.

Each plugin resides in its own subdirectory, which contains PHP files, optional assets, and metadata that define the plugin’s name, version, and activation state. WordPress scans this directory during initialization and populates the Plugins screen in the admin panel accordingly. Once activated, plugin files are executed within the runtime environment.

Only plugins located directly within /plugins/ can be managed via the admin UI, making this directory essential for structured, modular expansion of WordPress capabilities. Unlike core files, the contents of /plugins/ are safe for developer modification, version control, and deployment workflows.

/themes/

The /themes/ directory houses all visual and layout logic for a WordPress site, storing each installed theme in its own subfolder within /wp-content/. This includes the active theme and any inactive themes available for activation.

Each theme contains PHP template files, style sheets for styling, optional JavaScript and image assets, and a style.css file that includes metadata such as the theme name, author, and version. WordPress detects and loads these files to render the site’s frontend and populate the Appearance panel in the admin dashboard.

Because /themes/ is decoupled from core logic, it is the primary directory for developers to manage site appearance. All design modifications, custom templates, and frontend presentation logic reside here, forming the backbone of visual rendering.

/uploads/

The /uploads/ directory is the default media storage location within /wp-content/, containing all files uploaded through the WordPress admin, including images, PDFs, videos, audio files, and attachments. It is a dynamic, content-driven directory that grows over time, reflecting user-generated content and site evolution.

By default, WordPress organizes this directory using a year/month folder structure, which can be customized as needed. This convention supports chronological grouping and improves file management and media versioning.

Though developers typically do not interact with /uploads/ at the code level, it is critical for backup planning, storage strategy, and security auditing. The directory is publicly accessible in most setups, meaning improperly managed uploads can pose a risk, especially if file types or access rules are not properly restricted.

Given its role in storing site-specific media assets, /uploads/ should be regularly monitored, securely backed up, and, in high-traffic or enterprise environments, often offloaded to external storage or a CDN for performance optimization.

/mu-plugins/

The /mu-plugins/ directory (short for “must-use plugins”) is a specialized subfolder within /wp-content/ that WordPress automatically loads on every request, without requiring manual activation or user interaction. It is executed early in the load sequence, bypassing the standard plugin registration system.

Each PHP file placed directly in /mu-plugins/ is automatically loaded. Unlike the /plugins/ directory, WordPress does not scan subfolders here; only top-level files are executed. This behavior enforces a strict, minimal structure for predictable execution.

Developers use /mu-plugins/ to implement persistent functionality, such as environment-specific logic, security hardening routines, or system-level plugin overrides that must always be on and immune to user deactivation. Because these files are not visible in the admin Plugins screen and execute before standard plugins, they offer a high level of control but reduce transparency and can complicate maintenance.

What’s the Role of the /wp-includes/ Directory?

The /wp-includes/ directory contains the internal system libraries, procedural functions, core classes, and API handlers that power the runtime execution of every WordPress request, across both the frontend and the backend. It forms the backbone of the WordPress CMS, defining the shared logic that enables page rendering, data formatting, post querying, internationalization, template loading, and REST API communication.

This directory is automatically loaded during the WordPress bootstrap chain, starting foundational services that run before plugin or theme logic. While /wp-admin/ governs admin-specific UI, /wp-includes/ drives system-wide behavior, including the core logic used by both the dashboard and public site views.

As a core-managed component, /wp-includes/ is strictly non-editable. Developers must not modify any files here, as they are overwritten during WordPress updates. Despite this, the directory’s structure and contents remain critical to advanced development workflows: it is often the origin point when tracing filters, hooks, and function calls; it serves as the reference layer for debugging execution chains and understanding the system’s dependency map.

How Should Developers Maintain WordPress Files and Directories?

Core Files in /wp-admin/ and /wp-includes/ Should Not Be Modified

Files located in /wp-admin/ and /wp-includes/ are core-maintained components of WordPress and should not be modified under any development circumstances. These directories are automatically replaced or updated during version upgrades, meaning any direct changes are overwritten or lost and are likely to break compatibility with future releases.

Altering these files complicates debugging, undermines deployment integrity, and introduces unpredictable behavior in environments where stability and consistency are non-negotiable. Beyond version disruption, unauthorized changes hinder third-party support and prevent reliable troubleshooting.

Custom functionality, UI extensions, and system alterations should be handled exclusively through the plugin, theme, or hook architecture, designed precisely to extend WordPress without disrupting the core logic.

Maintaining strict separation between core files and custom logic is a foundational best practice that preserves version safety, supports reliable maintenance, and ensures the system’s long-term stability. In short: don’t modify, extend.

The /wp-content/ Directory Should Always Be Backed Up

The /wp-content/ directory contains the most valuable and irreplaceable parts of a WordPress website: themes, plugins, uploaded media, and all site-specific logic. Unlike /wp-admin/ or /wp-includes/, which can be restored from clean installations, this directory preserves everything unique to the project.

If lost or corrupted, the consequences are immediate: site design and layout are destroyed, plugin data and custom logic are unrecoverable, and media content vanishes unless it was backed up independently. This makes /wp-content/ the primary backup target in any development, staging, or production environment.

Because it contains user-generated and developer-authored content, this directory must be treated as non-negotiable in backup routines, serving as a vital node for disaster recovery, deployment continuity, and content integrity.

Developers Should Use Git for Version Control in /wp-content/

The /wp-content/ directory is the central point for all code-based development in WordPress, making it the only valid scope for applying Git version control. Since this is where developers maintain custom themes, plugins, and functional assets, it should be tracked in a Git repository to ensure traceable, reversible, and collaborative coding practices.

Version control in this directory preserves development history, supports rollback during errors, and enables team collaboration without conflict. It also provides clear audit trails during deployment and staging workflows, aligning tightly with the WordPress code standards.

Unlike core files in /wp-admin/ and /wp-includes/, which are excluded from version control because they are system-maintained, /wp-content/ is development-owned. Every custom line of code introduced here should be versioned, reviewed, and maintained as part of any professional software project.

The license.txt and readme.html Files Should Be Hidden in Production

The files license.txt and readme.html are included by default in every WordPress installation and provide metadata about WordPress licensing and versioning. While they serve a purpose in development environments, they add no functional value in production and introduce unnecessary exposure.

By default, these files are publicly accessible and frequently scanned by bots to determine a site’s WordPress version, which can lead to targeted attacks if the version is outdated or known to have vulnerabilities. In particular, readme.html is often flagged in security audits for version disclosure.

These files are not required for WordPress operation. Removing or restricting access to them in live environments helps reduce attack surfaces and aligns with best practices for file hardening and deployment hygiene.

If a file doesn’t serve an operational role and instead exposes metadata, it should not remain visible in production.

Contact

Don't like forms?

Shoot us an email at [email protected]